Area History

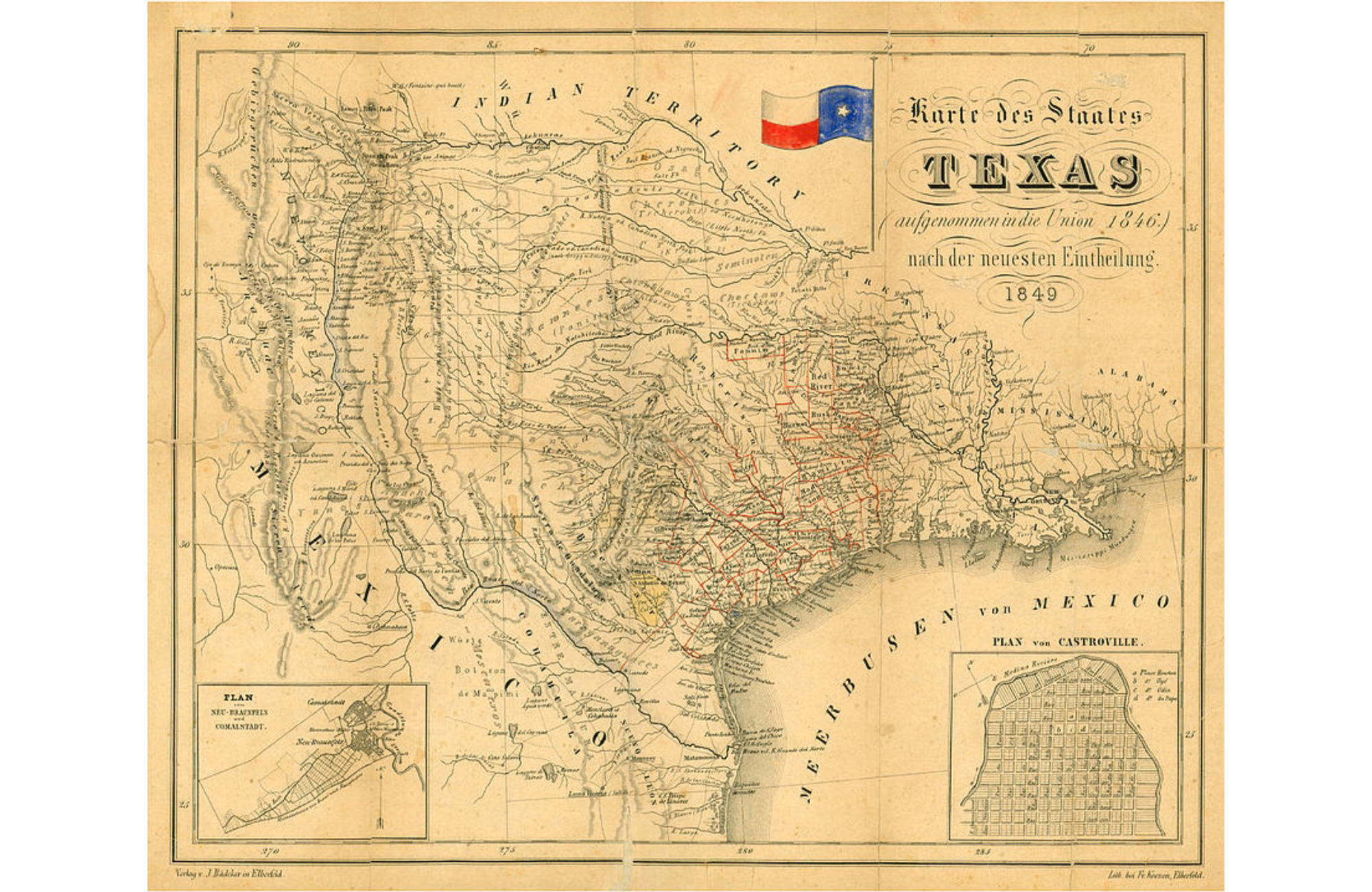

Historical Background of the Texas Hill Country

Immigration to Texas

German Settlers in the Texas Hill Country

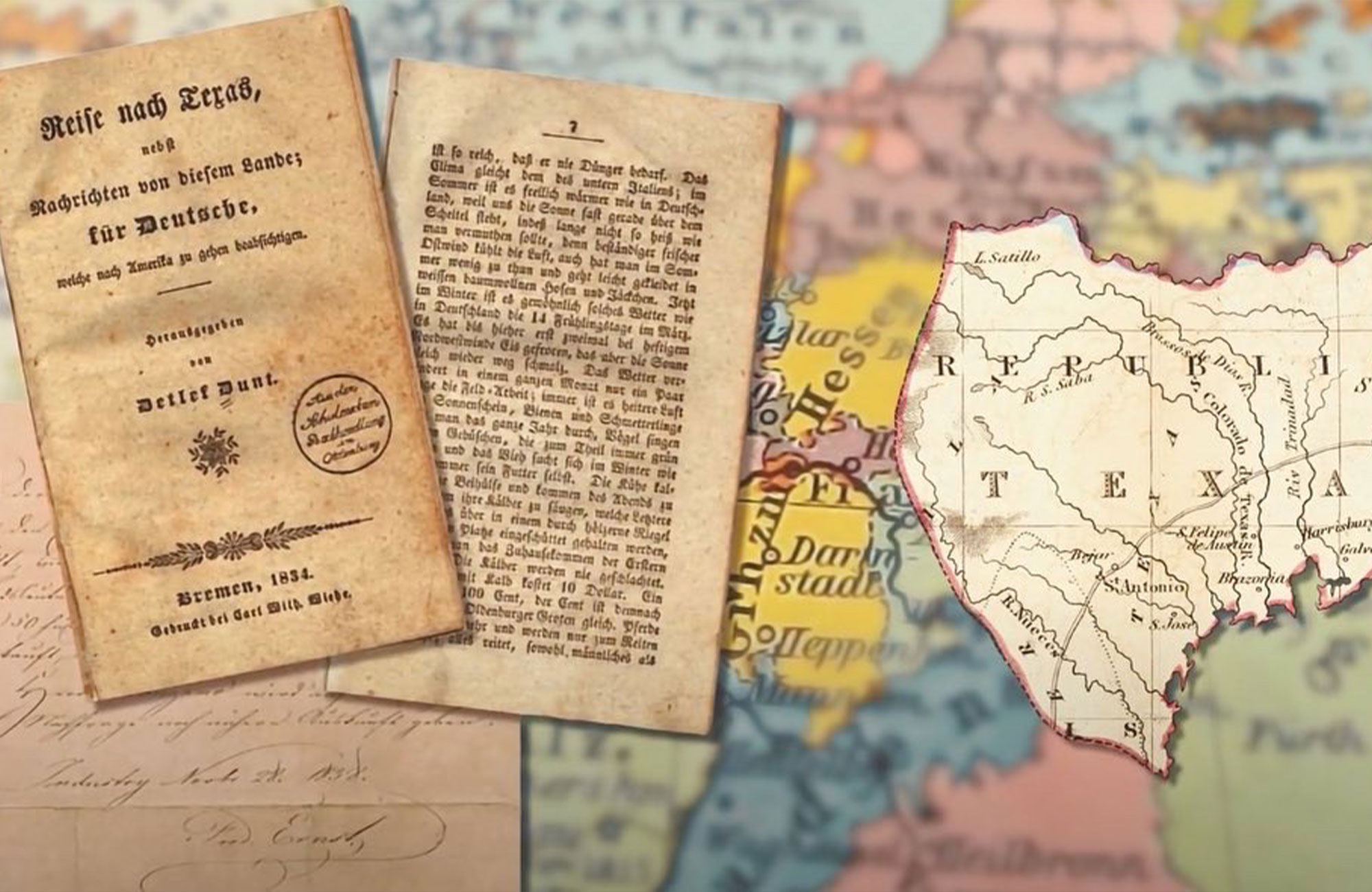

The first concerted effort to bring German settlers to Texas came in 1831, when Johann Friedrich Ernst (aka Friedrich Dirks), from the Grand Duchy of Oldenburg, received a land grant in Stephen F. Austin’s colony, near Industry, Texas. Ernst wrote lengthy letters to friends in Germany, and through these “America letters” he reached and influenced other prospective migrants describing a land with a winterless climate like that of Sicily while abundant in game, fish, and soil that was fertile and rich.

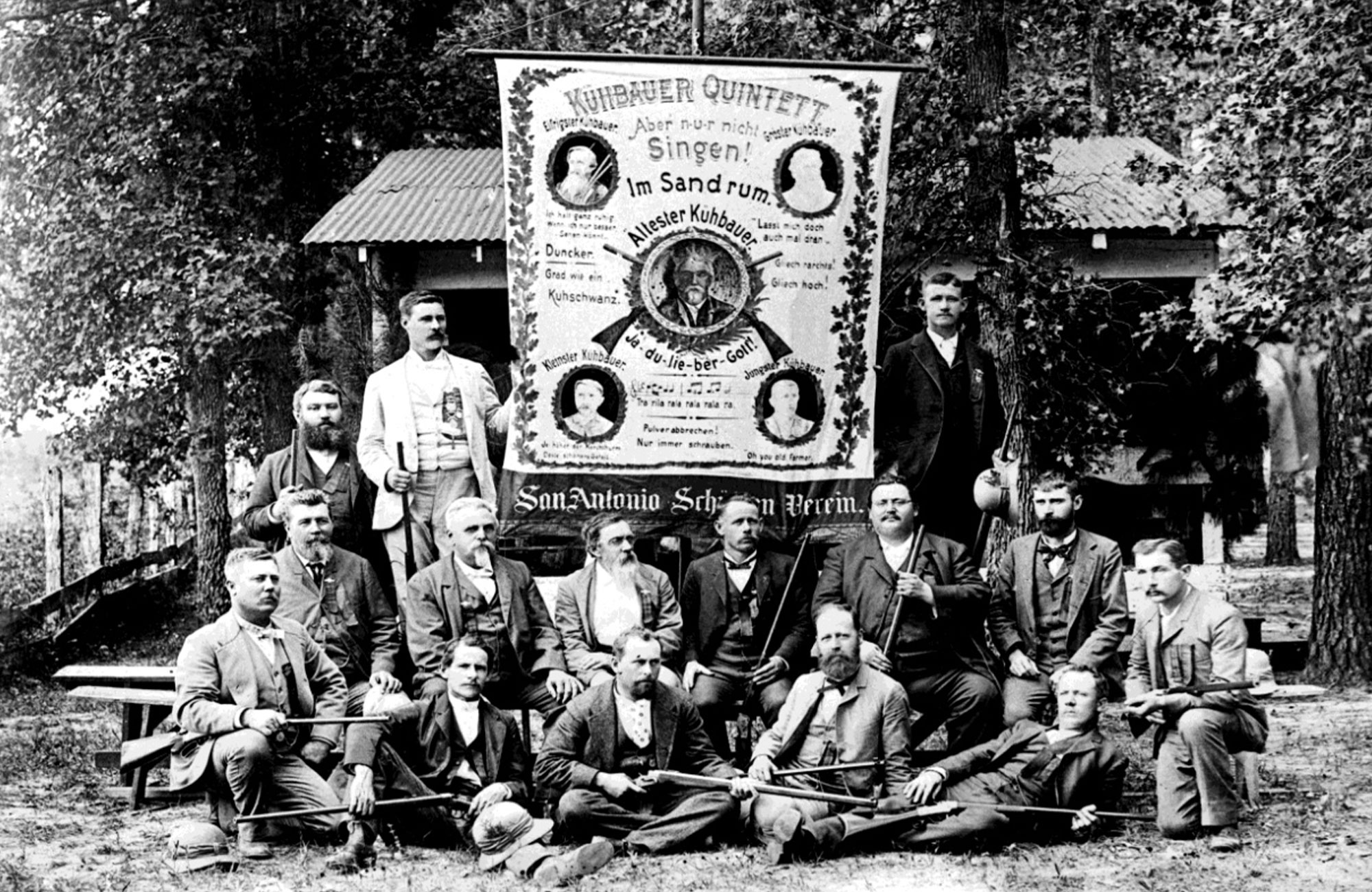

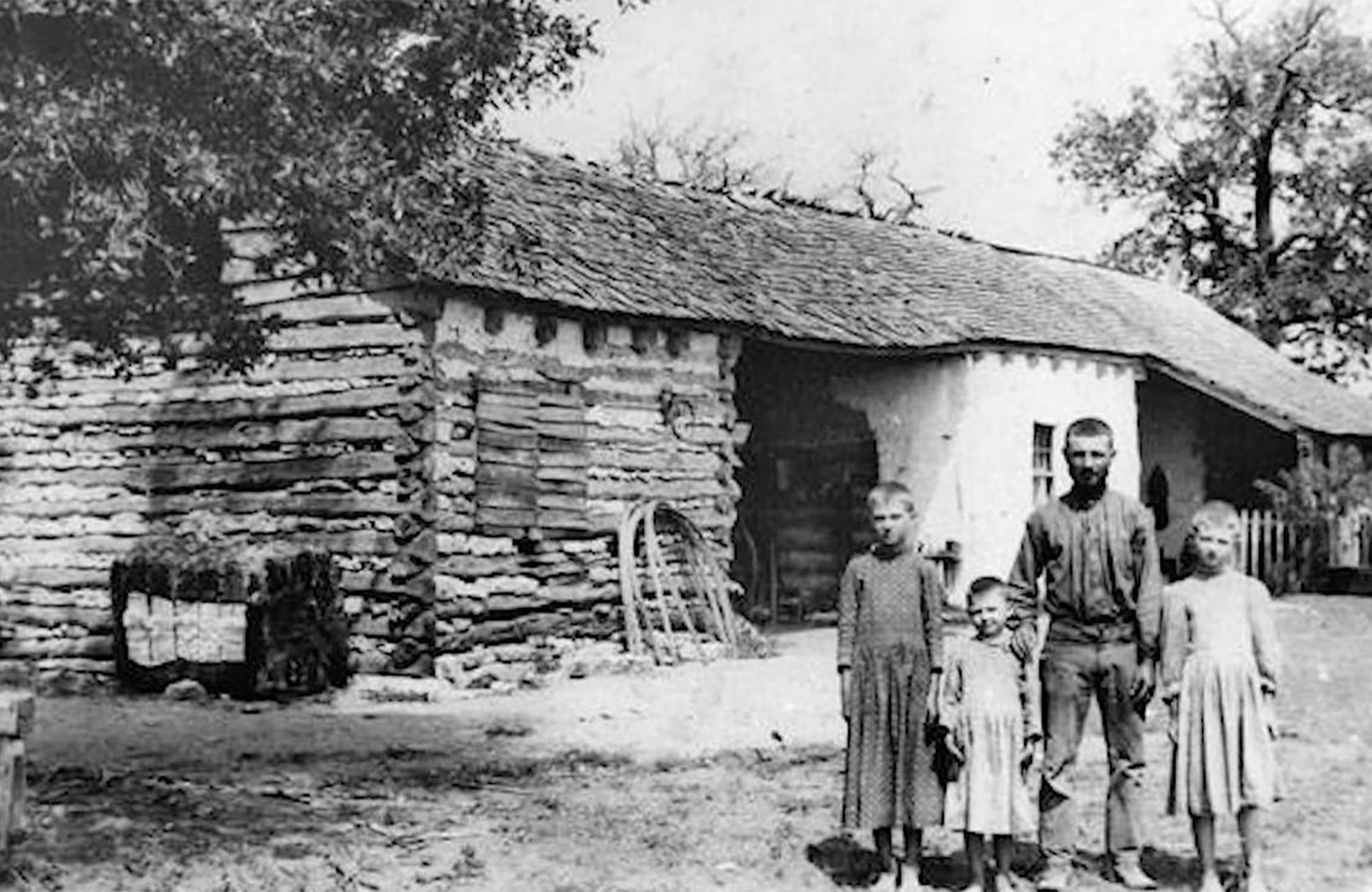

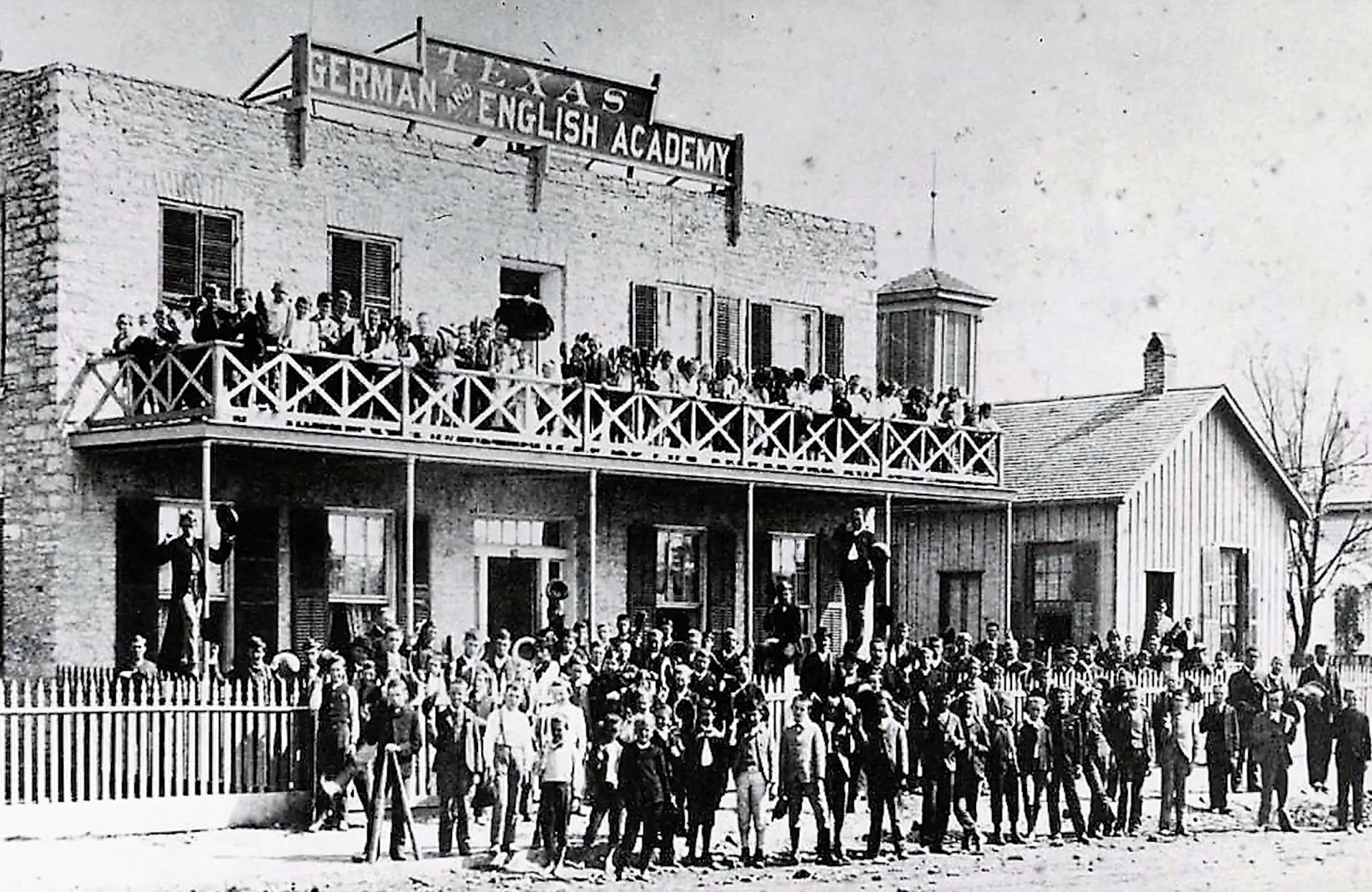

Unlike Irish immigrants, who spoke English and assimilated more quickly into the larger cities, the “Deutschamerikaner” preferred congregating in communities outside of the towns where they could speak their language freely and preserve their heritage.

It was said that Mexico had invited them to move to their country, but they were determined “to enjoy” the republican institutions to which they were accustomed in their native land.

Subsequent publicity about Texas and the republic’s independence soon after drew the attention of minor noblemen in the German states to the idea of investing in Texas.

These “German Texans” founded the towns of Bulverde, New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, Boerne, Pflugerville, Walburg, Comfort and Castell (started in 1847) in the Texas Hill Country, Muenster in North Central Texas and Schulenburg, Brenham, Industry, New Ulm and Weimar to the east.

Nineteenth Century Freethinkers

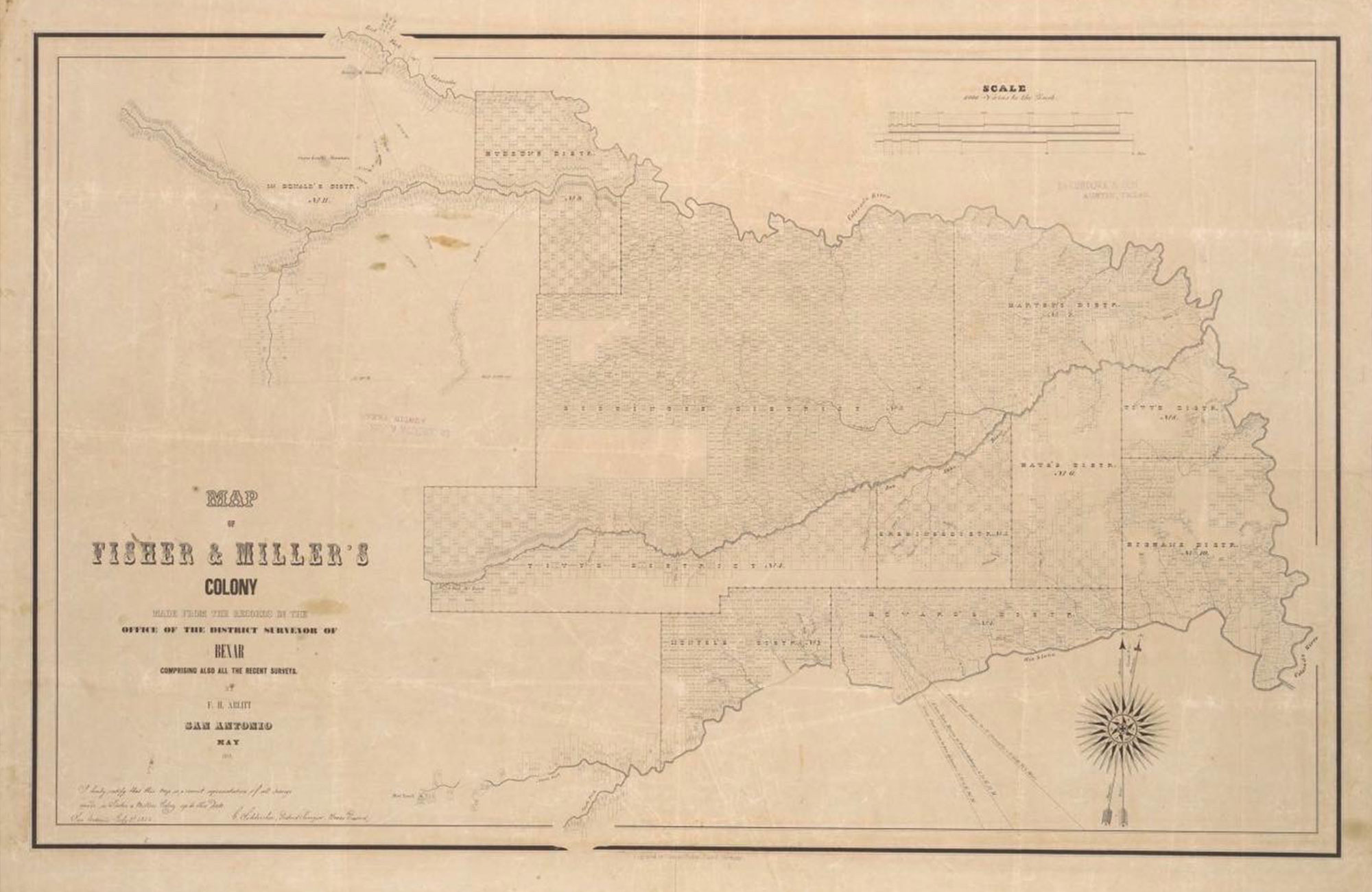

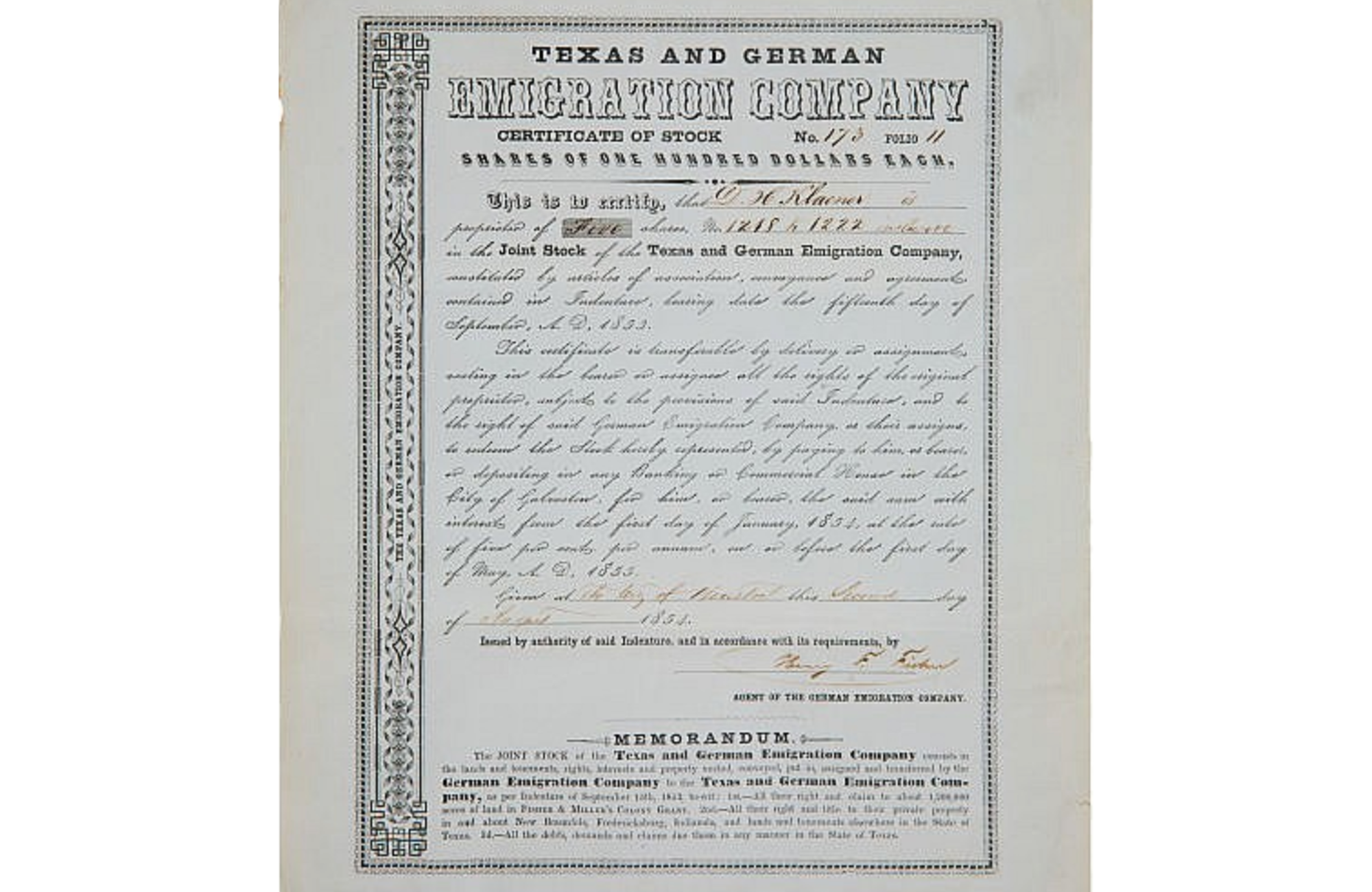

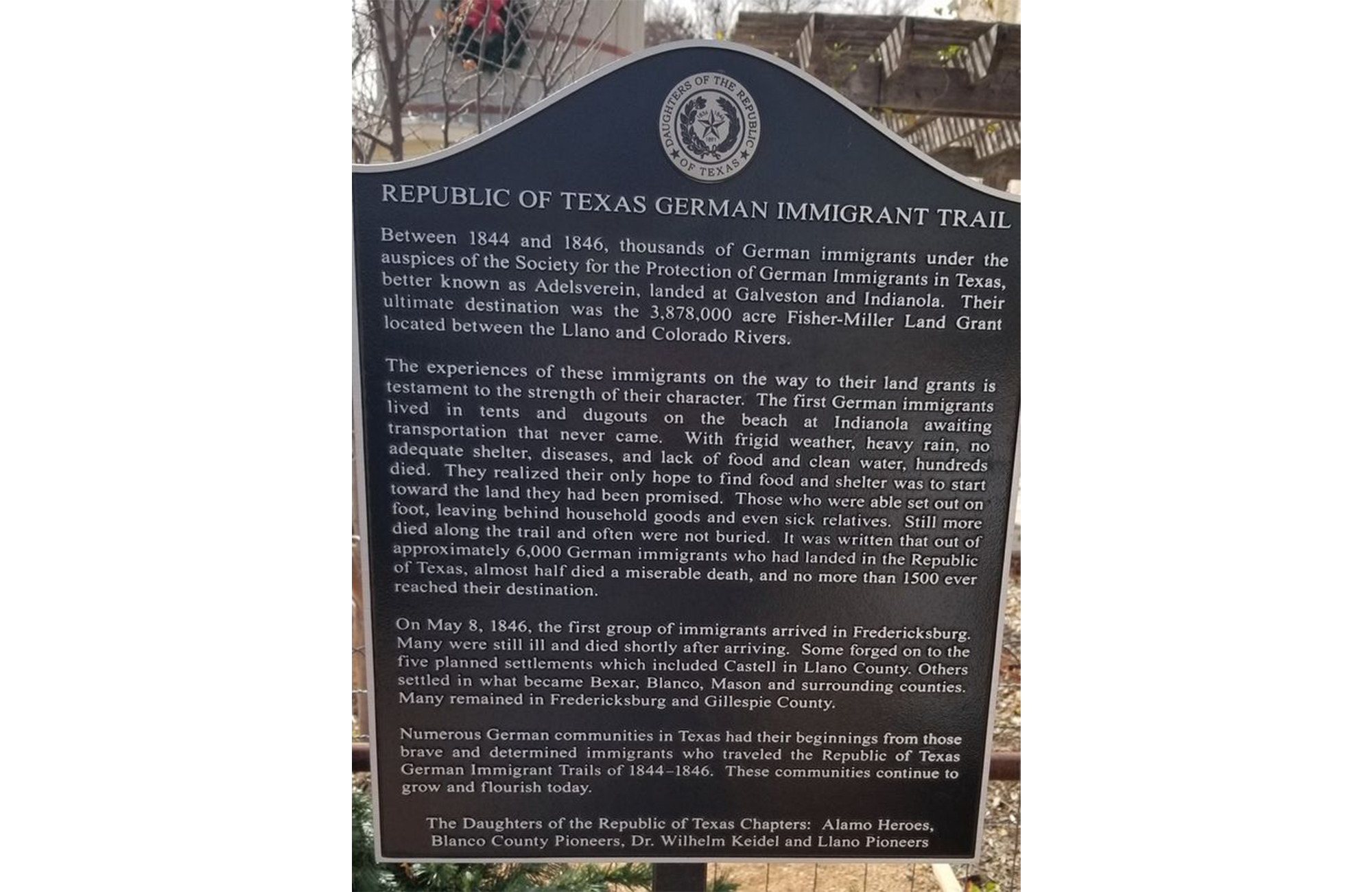

The Fisher-Miller Land Grant, made by the newly formed Republic of Texas on June 7, 1842, was formed from a petition on 3,800,000 acres between the Llano and Colorado rivers—made by Henry Francis Fisher, Burchard Miller, and Joseph Baker—permitted immigrant families of German, Dutch, Swiss, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian ancestry to settle in Texas.

Originally contracted under the auspices of the San Saba Colonization Company, the agreement allowed for the introduction of 600 families and single men within 3 years.

At the outset, Fisher was able to bring 96 immigrants to Texas himself before selling part of his (and Miller’s) interest in the colonization contract on June 26, 1844, to the Adelsverein, or the Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas.

The Adelsverein, also known as the Mainzer Verein, the Texas-Verein, and the German Emigration Company, was officially named the Verein zum Schutze deutscher Einwanderer in Texas (Society for the Protection of German Immigrants in Texas).

Formed in 1842 by twenty-one German noblemen in Biebrich, Germany its purpose was to acquire land in Texas and encouraging German emigration. But by 1847 the society was on the brink of bankruptcy and only managed to remain in business after installing new management and a name change to German Emigration Company.

1801-1850

Count Carl Frederick Christian of Castell-Castell

Inspired by books that he had read about Texas and the Texans’ struggle for independence, in the year 1842, a Count Carl Frederick Christian of Castell Germany (Bavaria) organized a society for the purpose of directing emigration to Texas from Germany. Amongst 21 noblemen, they met at Biebrich-on-the-Rhein, near Mainz, and formed the association called the Adelsverein.

Count Carl descended from a long line of Franconian knights and nobles dating back to the 13th century. Under his management the German Emigration Company society was reorganized into a stock company, and eight months later the society’s first shipload of immigrants disembarked at Port Lavaca, Texas. He led the society through its formative years as well as during the financial difficulties in the mid-1840s of settling immigrants into the Fisher-Miller Land Grant.

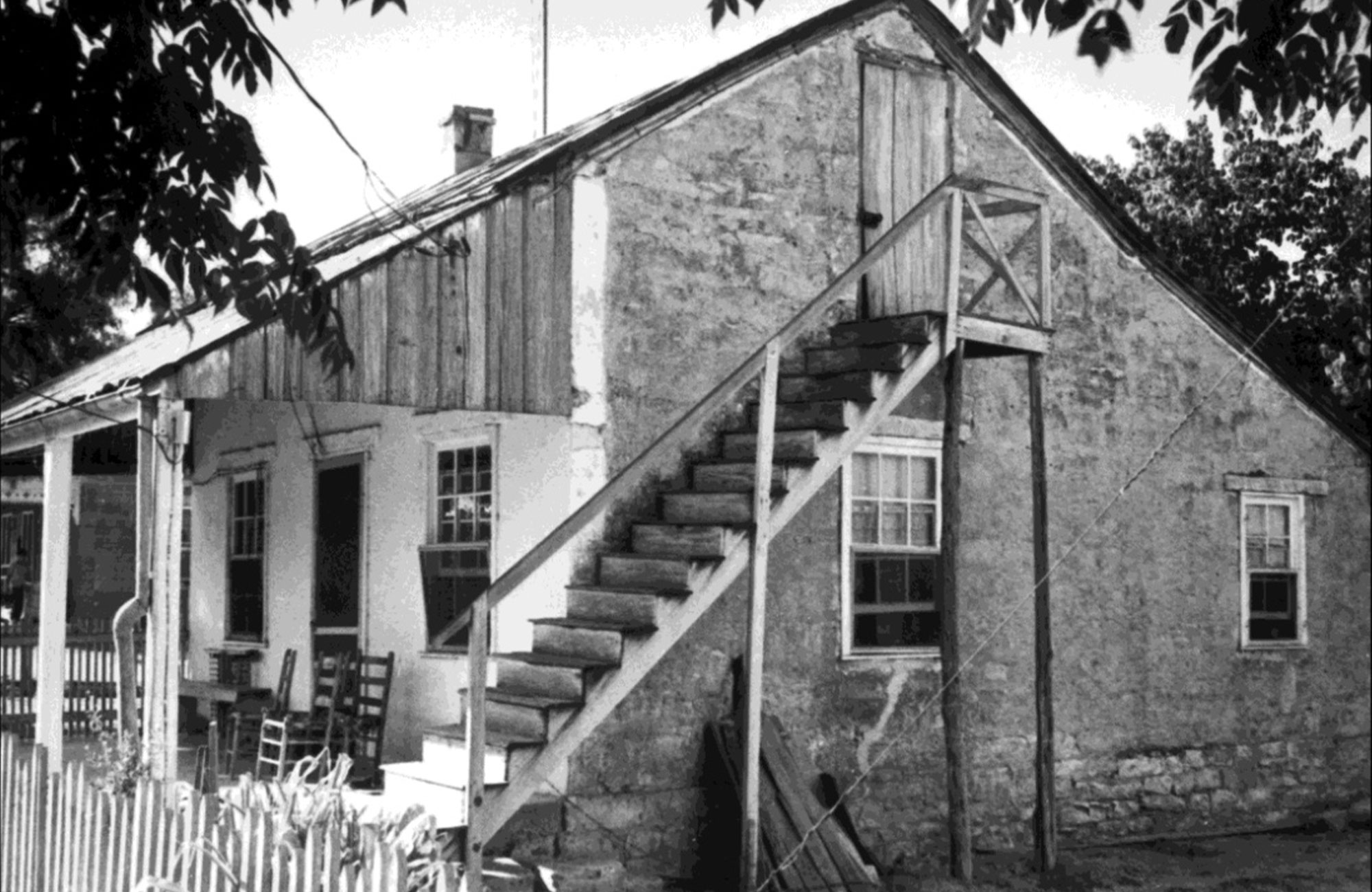

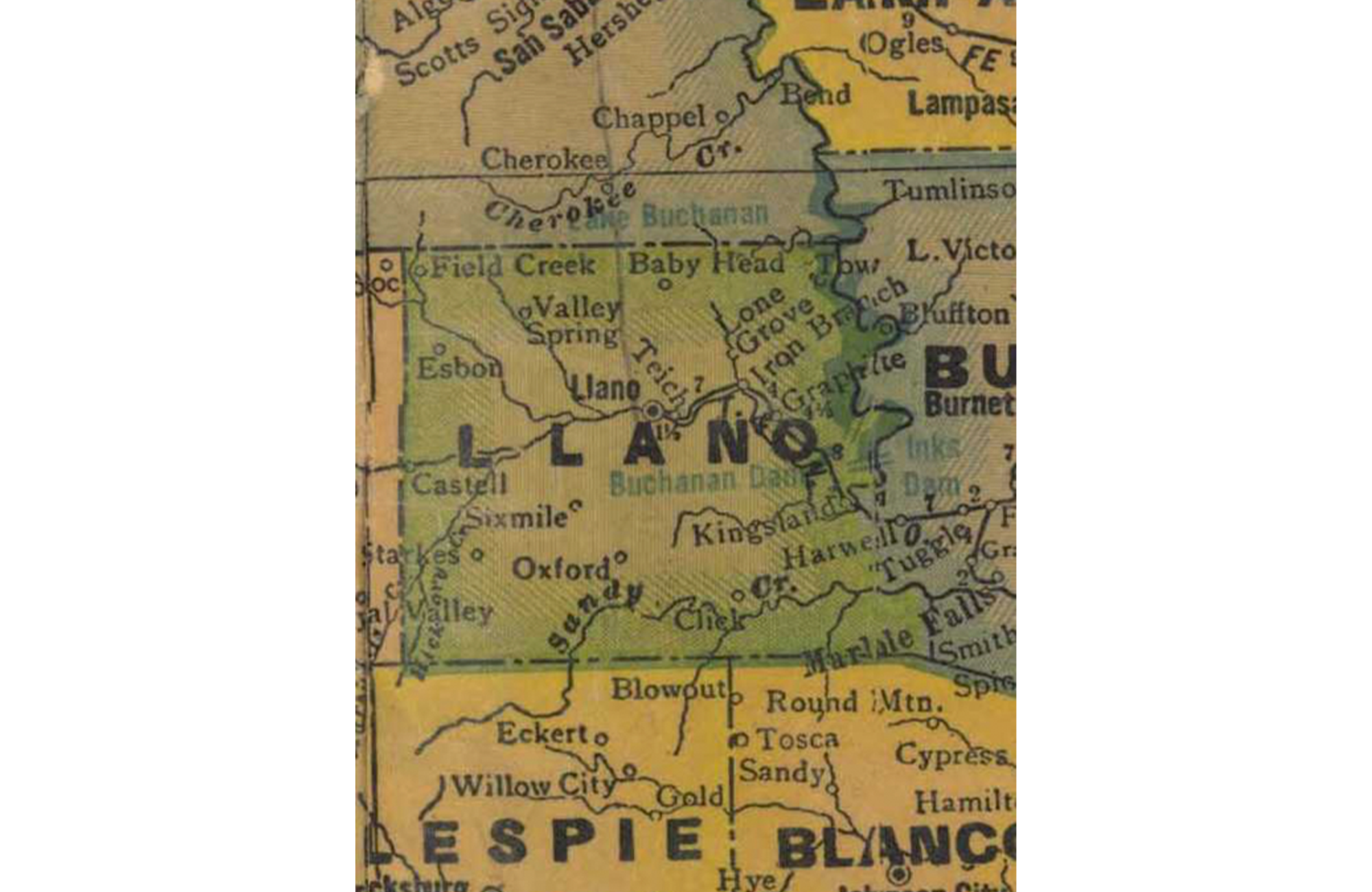

Count Carl had an intense personal interest in the success of colonization and as a result the town of Castell was in named in his honor. Castell now has the distinction of being the oldest surviving settlement in Llano County. And although the town is now officially located on the south bank of the Llano River, it originally began on the north bank in 1847 with a USPS post office opening in 1872 which still exists today, right outside our gates!

Failed Settlements & Ghost Towns

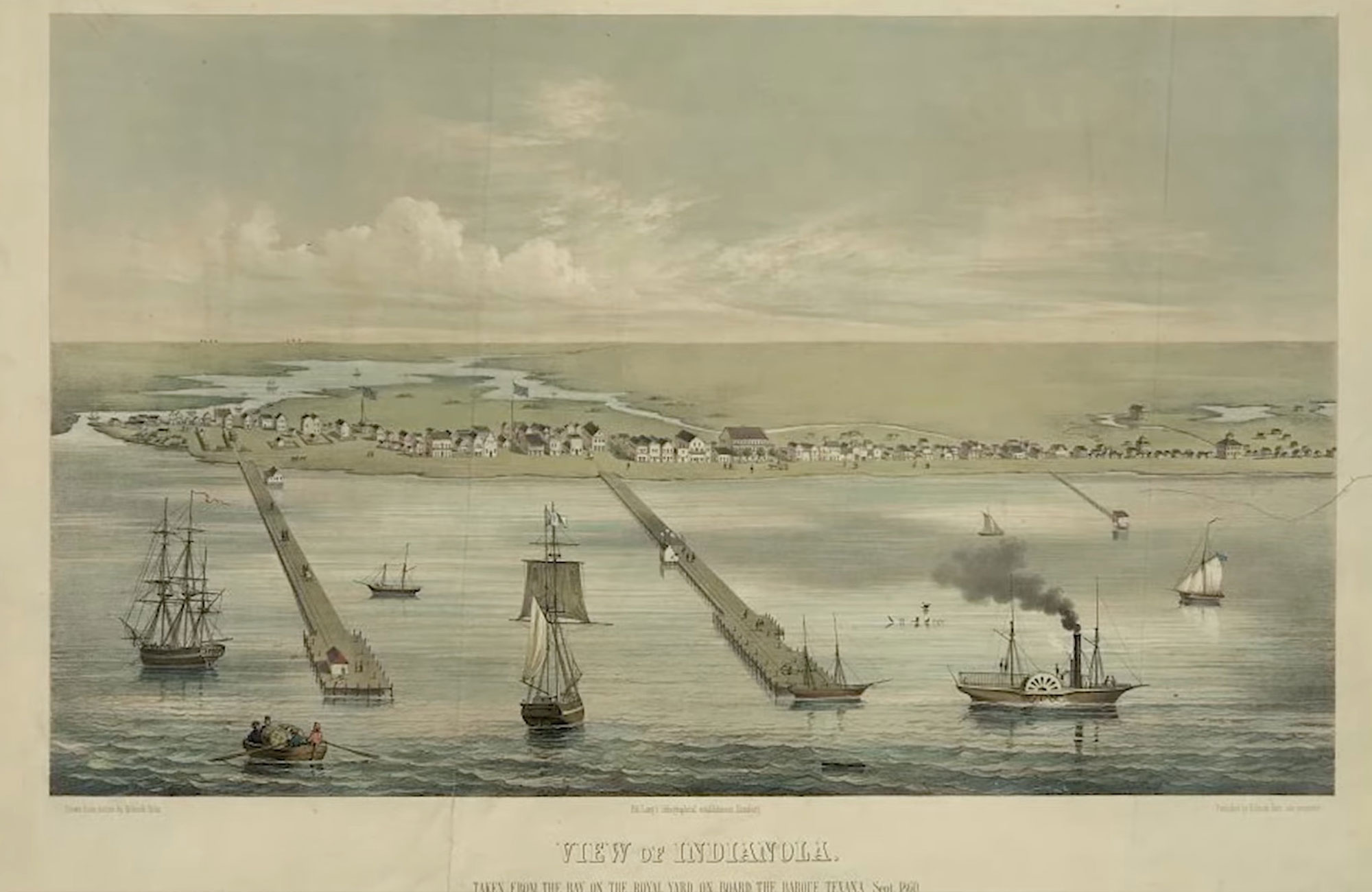

Indianola, Texas was once the main port of entry for German Immigrants to the Texas Hill Country, but today remains a ghost town identified by Recorded Texas Historical Landmark #2642.

Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels, representing the Adelsverein, selected “Indian Point” in December, 1844 as port of entry for the Verein colonists. Prince Solms renamed the port “Carlshafen” in honor of himself, Count Carl of Castell-Castell and Count Victor August of Leiningen-Westerburg-Alt-Leiningen whom Solms claimed had been christened Carl.

The name of the settlement changed to Indianola in 1849 by combining the word “Indian” with “Ola”, the Spanish word for “wave”. However, German immigrants continued to refer to the community as Carlshaven (Carl’s Harbor) in honor of Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels.

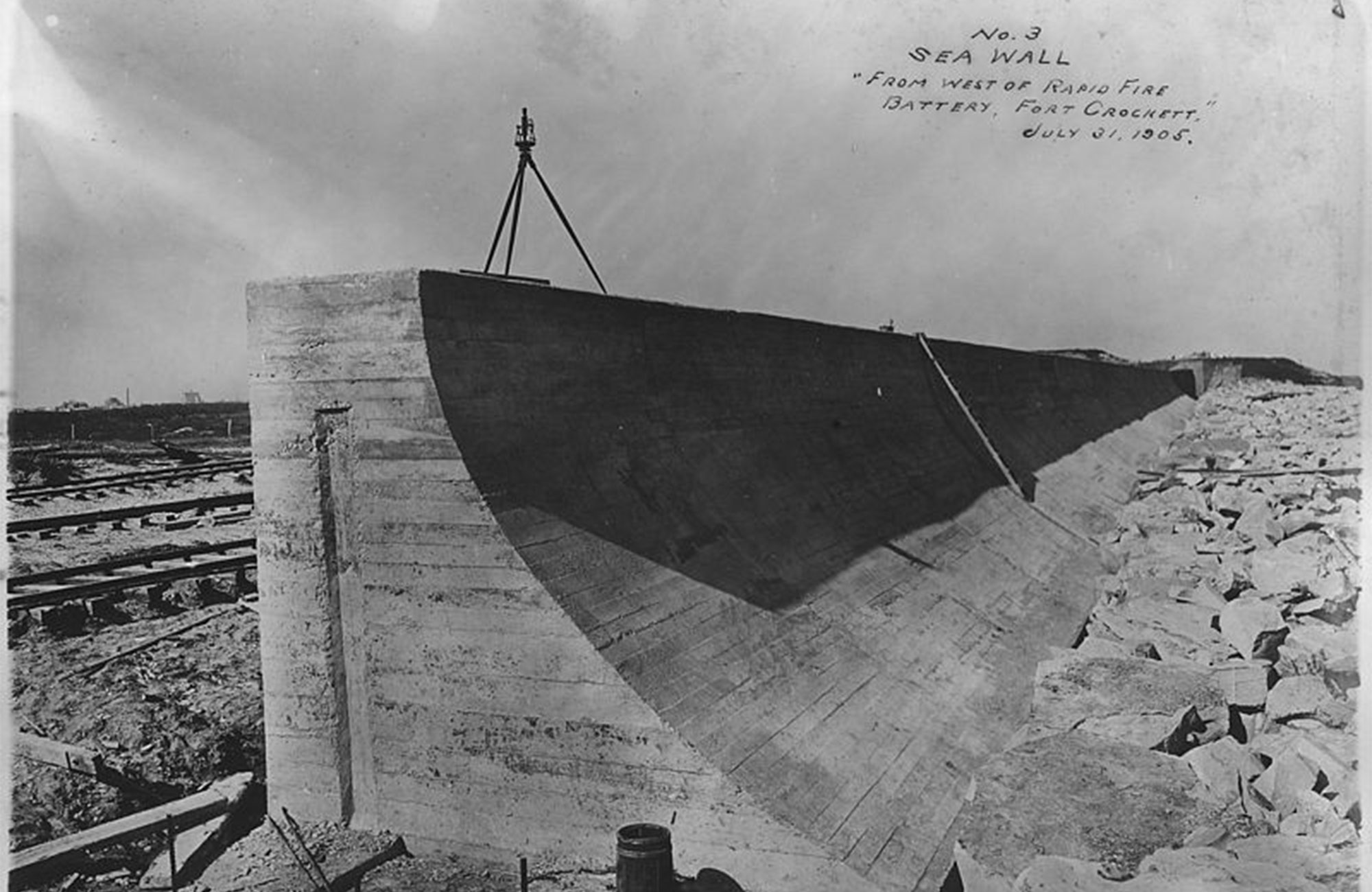

From its founding, Indianola served as a major port on Matagorda Bay, achieving a population of 5,000 before a hurricane struck on September 15, 1875 killing 150-300 and destroying the town. Indianola was rebuilt, only to be wiped out again on August 19, 1886, by another hurricane and subsequent devastating fire.

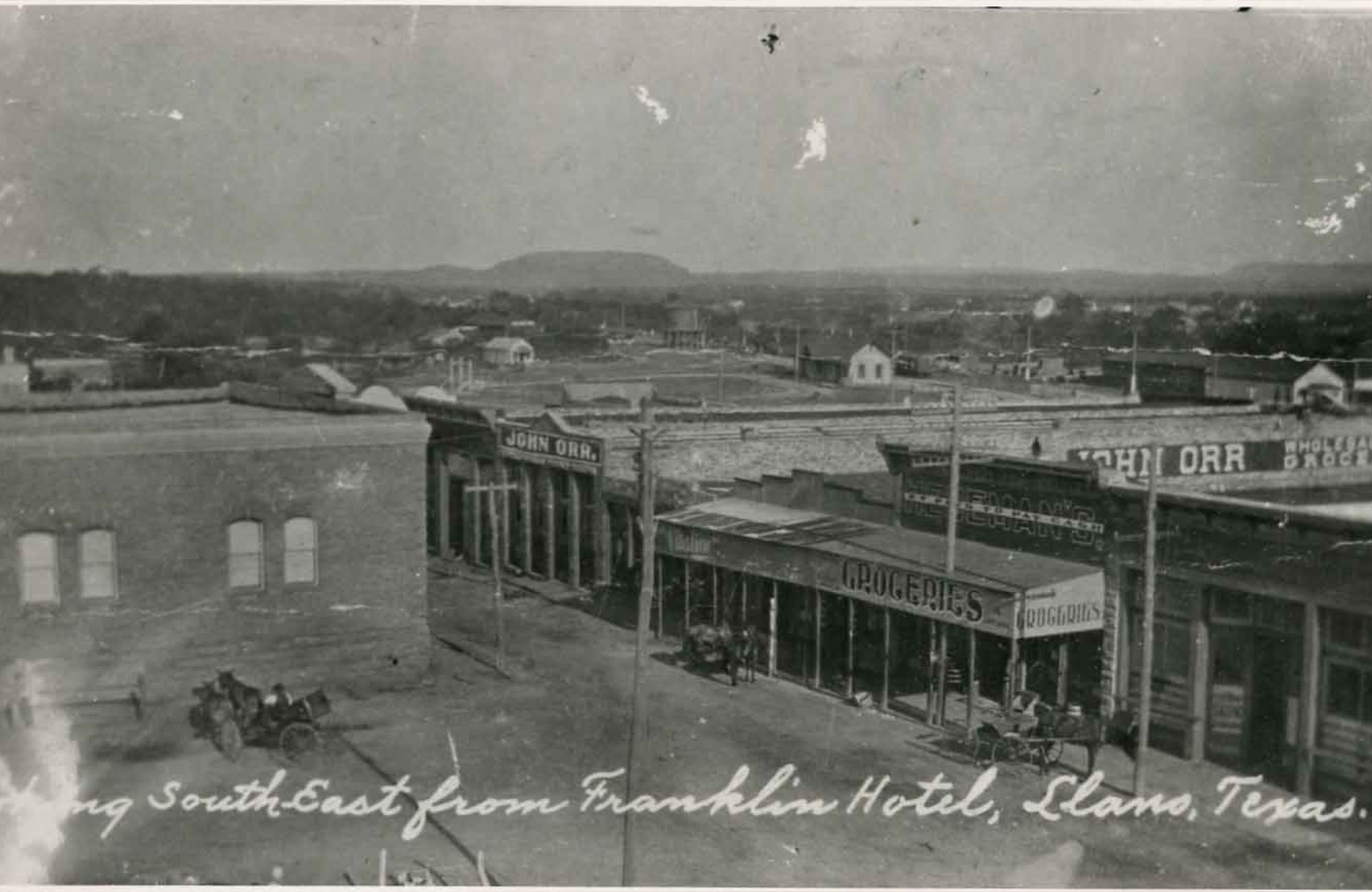

Llano County & surrounding area

Native Tribes & Early Settlers

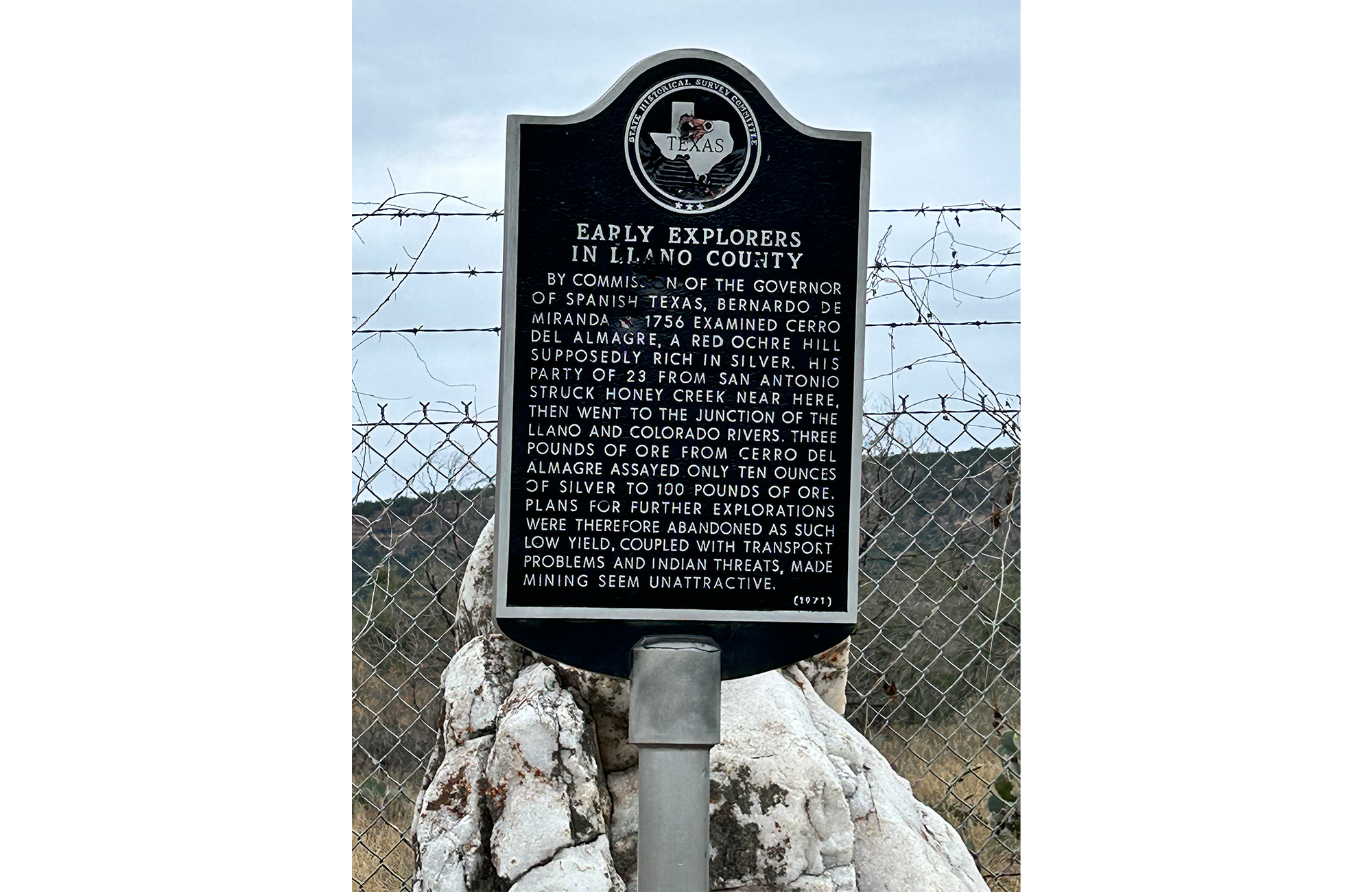

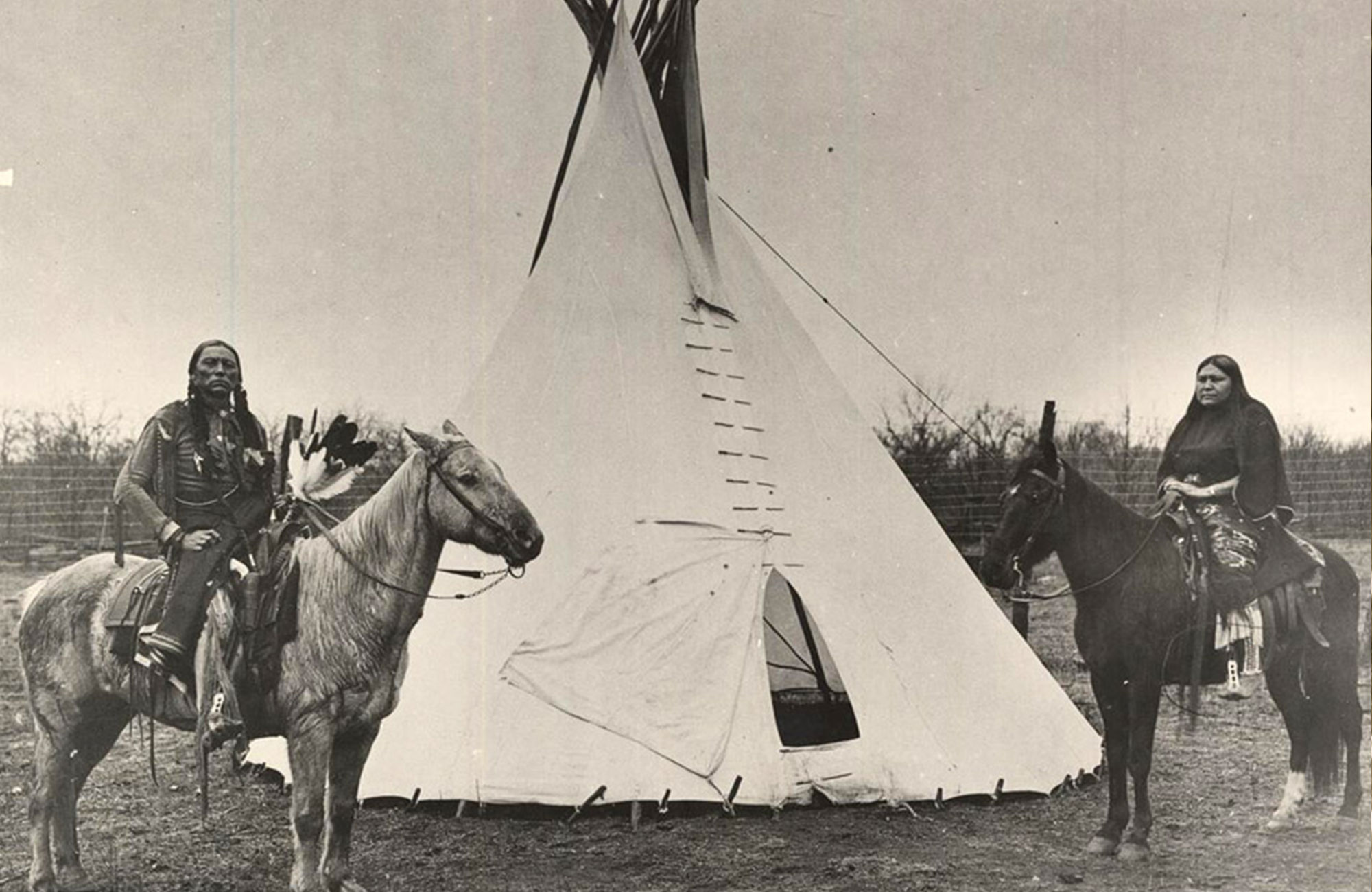

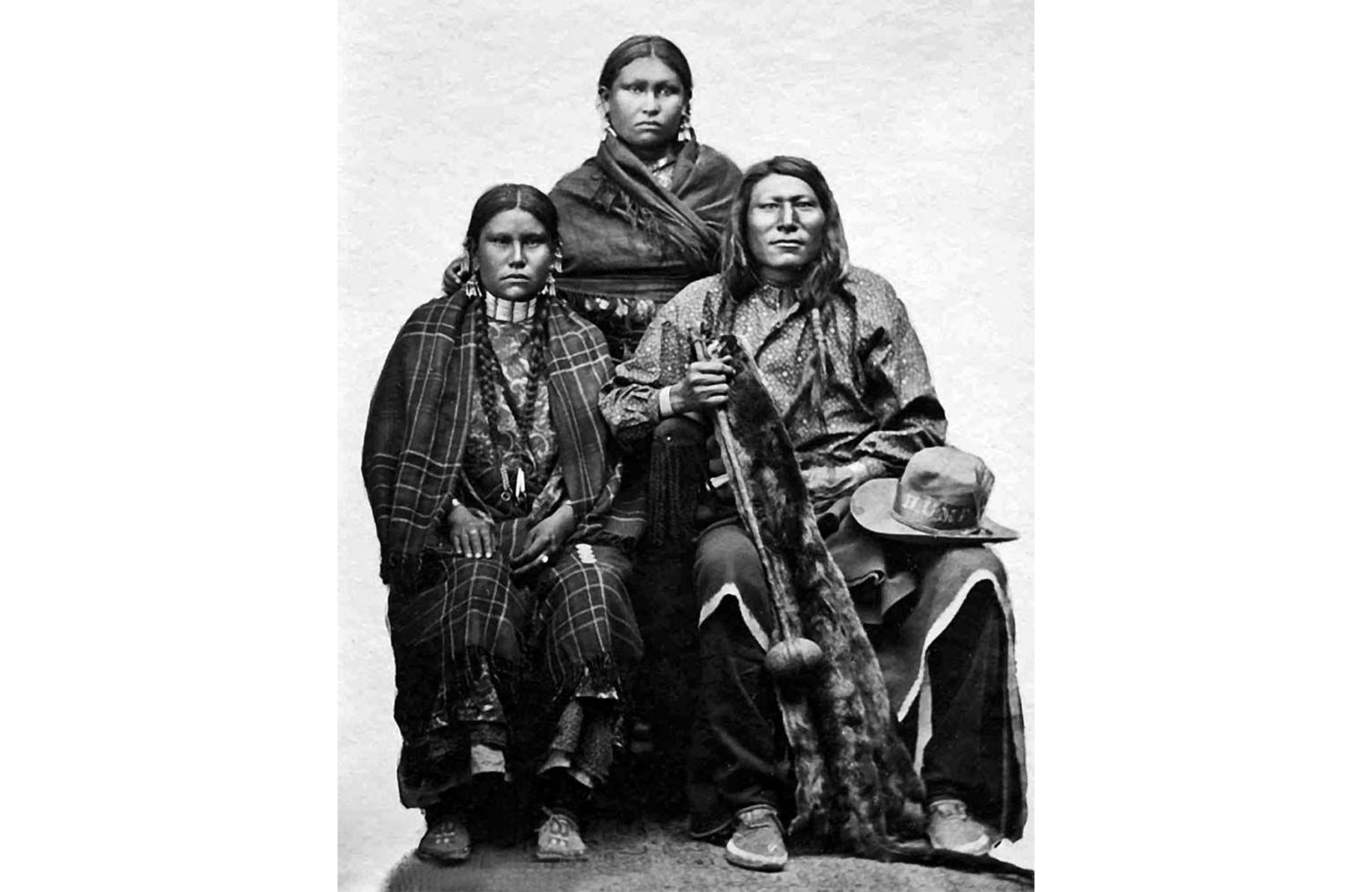

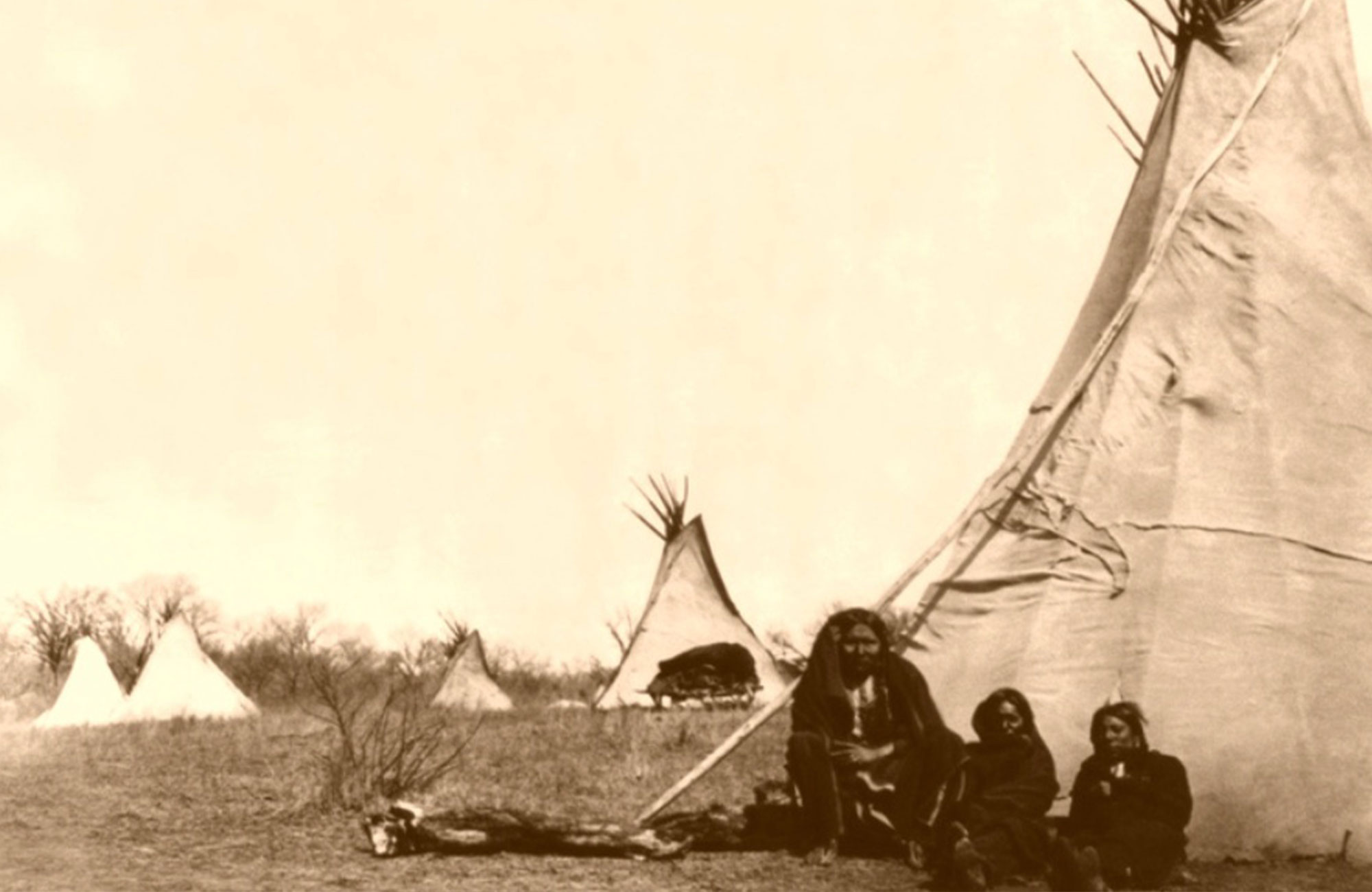

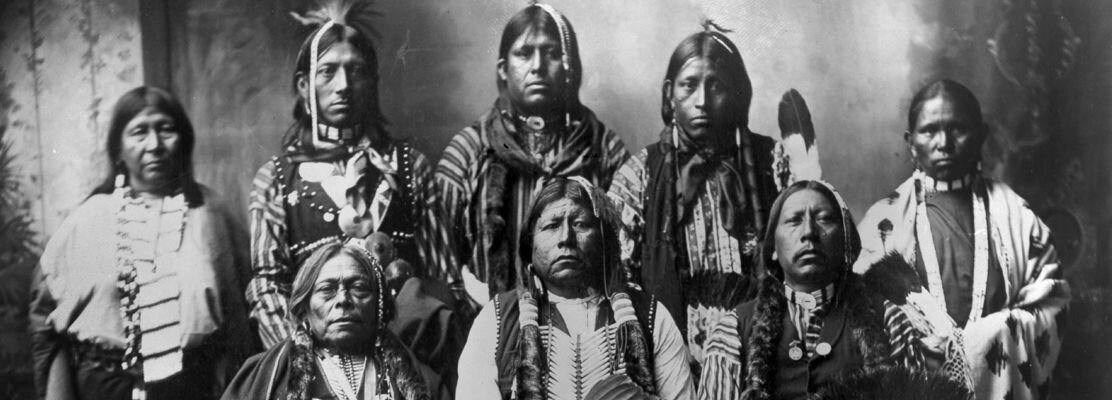

The Tonkawa Native American Tribe was living in the Llano area when the first Europeans arrived in the vicinity in 1535. Spanish explorer Alvar Nunez Cabeza De Vaca led an expedition to explore the vast, uncharted region—later supplanted by the Apache Indians and in turn, they were displaced by the Comanche Indians. It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that European settlers found the area. Until that time, the land was known as the West Texas Frontier-Indian Territory, or Comancheria by the Comanche Indians—the dominant group in the Southwest at that time.

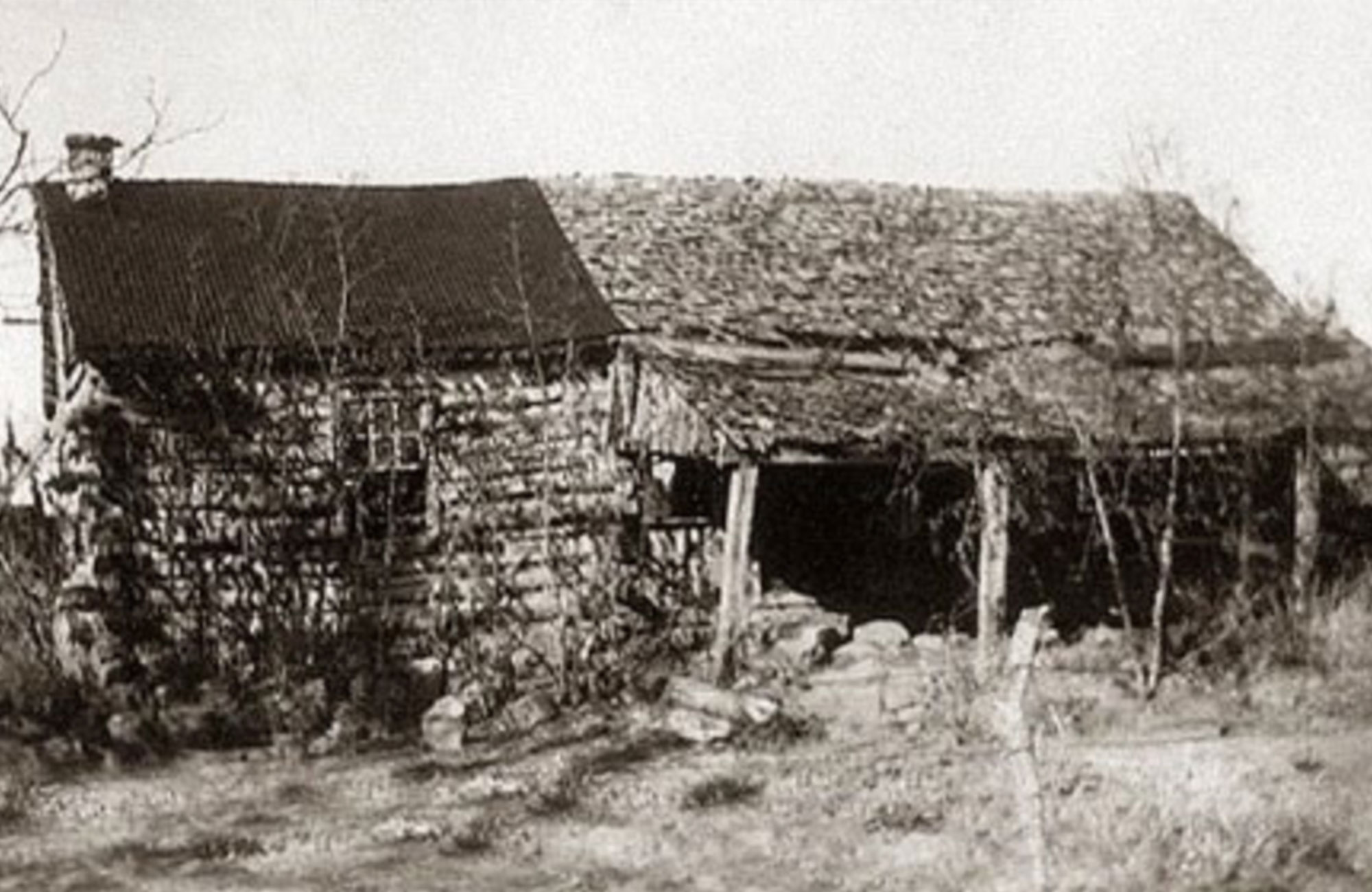

Eventually, the first European residents to the area were brought by the Adelsverein, a group of German noblemen organized to aid emigration to Texas starting in June of 1844 on the territory purchased known as the Fisher-Miller Land Grant. Two of the first settlers were Henry Durst and August Liefeste – ancestor to Randy Liefeste owner of the Castell General Store.

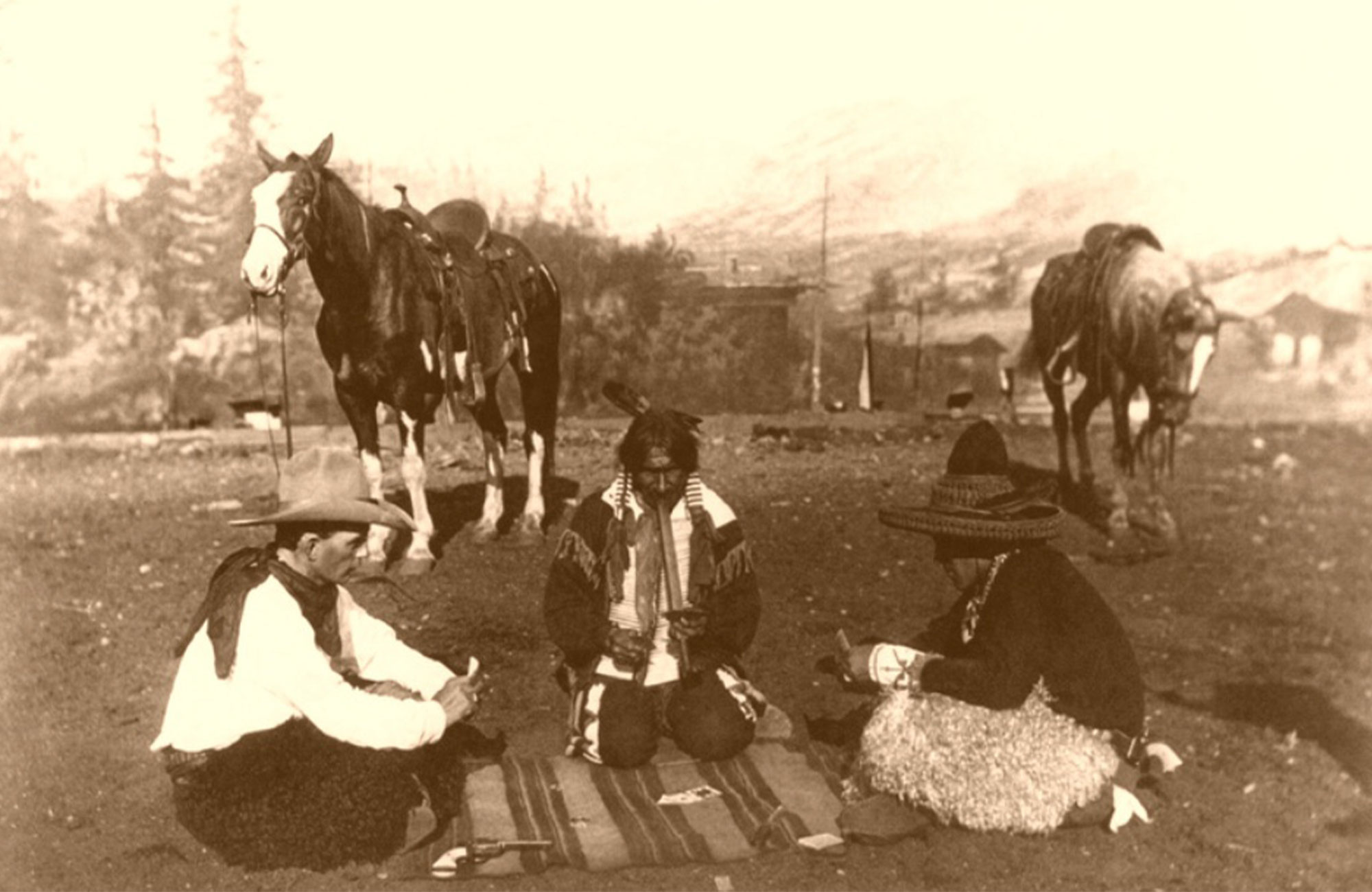

In 1847, the 3.88 million-acre Fisher-Miller grant purchased by the German Immigrant Society had to be surveyed by the fall, or it would be forfeited. What the immigrants did not know was that the Comanche, the most feared of tribes, claimed that area as their hunting grounds as part of Comancheria. Making peace with the Comanche became the responsibility of John O. Meusebach, the 33-year-old commissioner-general of the immigrant group.

Meeting with Chief Ketemoczy of the Penetaka Comanche, Meusebach explained his friendly intentions, saying he represented towns that would welcome them. In return, he expected hospitality from his Comanche neighbors.

The Chief dubbed the red-haired Meusebach “El Sol Colorado” (Red Sun) and promised to summon the chiefs of the western bands of Comanche (Buffalo Hump, Santa Anna, Old Owl) to a peace council on the San Saba River at the next full moon.

On May 9, 1847, the treaty between the German Immigration Society and the Comanche nation was signed in Fredericksburg by 6 Comanche chiefs, Meusebach and 7 others. The Meusebach-Comanche Treaty was unique: The US government had no part in it; Despite a few infringements, the agreement is one of the few pacts with Native Americans that was never broken.

The original treaty document was eventually returned to Texas from Germany in 1970 by Mrs. Irene Marschall King, the granddaughter of John Meusebach. The document was presented to the Texas State Library in 1972, where it remains on display. Previously, in 1936, a Recorded Texas Historic Landmark, Marker number 991, was placed in San Saba County to commemorate the signing of the treaty and which was officially recognized by the United States government.

Comache Creek

Only 10 miles SW from El Castell you will find “Comanche Creek” which feeds into the Llano River, rising a half mile southwest of Mason Mountain and running southeast for 20 miles. And since it’s Native American Heritage month we thought it would be interesting to highlight the Comanche Tribe – who ruled the area coined by the Spanish conquistadors, Comancheria, from 1700 to 1874.

Like all Plains Indians, the Comanche were nomadic, venturing as far north and west as the Llano Estacado which was a place of extreme desolation, a vast, trackless, and featureless ocean of grass. Their lives were built on two things, really — war and buffalo. They hunted primarily the southernmost part of the high plains, and, once they got the horse from the Spanish, buffalo hunting became easier for them.

They were the richest of all plains bands in the currency by which Indians measured wealth — horses — and in the years after the Civil War managed a herd of some 15,000.

Native American History & Folklore

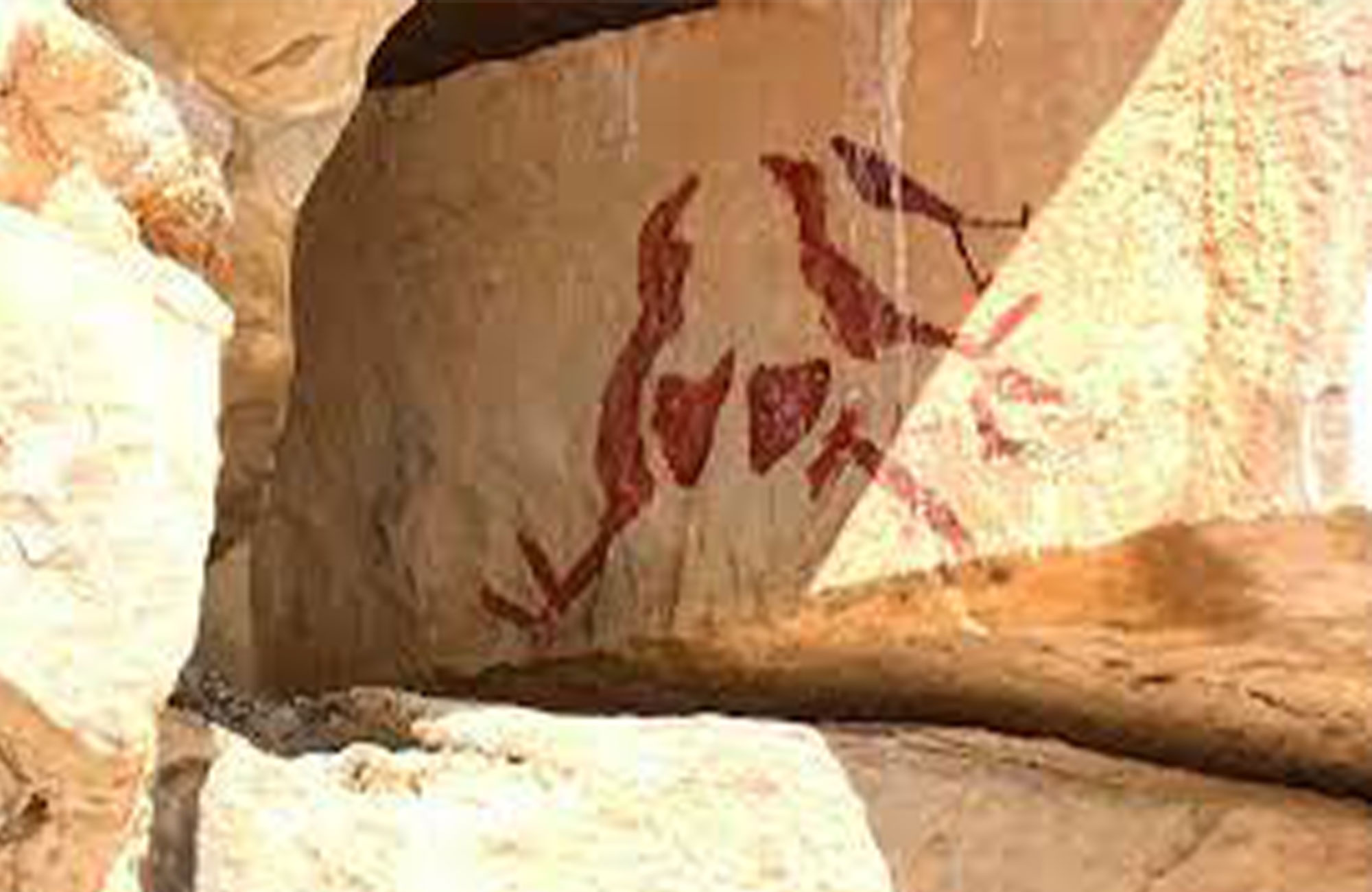

The Painted Rocks

Said to be the largest Native American site in the USA, “The Painted Rocks Native American Pictographs” located in Paint, Texas is only 1h 15m NW of Mason, Texas—so an easy day trip from @castelltexas.

Located just north of the Concho River near the small Texas town of Paint Rock, you will find limestone cliffs hosting over 1,500 pictographs in a variety of colors that include animal, human figures, geometrics, and handprints—all pigments derived locally and from nature. A rough date places the earliest pictographs around 1,000 years old but, the site was used repeatedly over the millennium. The pictographs, although often difficult to decipher, reveal clues about the inhabitants who occupied the country up to the arrival of Europeans. In addition, an estimated 1,500 pictographs are scattered across a half-mile of rock.